Resources, consultancy and training on integrating health, care and related services. Includes guides, models and evidence to support local areas, integrated care organisations, sustainability and transformation plans, care and health providers and commissioners.

Hospital discharge recording

Research on hospital discharge outcomes for working age adults, with insights and recommendations discussed.

Delivering integrated care

Demonstrating what good looks like in integrated care – research, practice and guidance.

Webinars on integration

These webinars look at the information, guidance and tools being prepared for publication as part of the NHS England ICS Implementation Programme.

Leadership

Developing leadership skills and managing strategy and governance in an integrated care system.

Intermediate care including reablement

Intermediate care can deliver better outcomes and reduce the pressures on hospitals and the care system.

Integrated care research and practice

This resource aims to support the planning, commissioning and delivery of coordinated person-centred care.

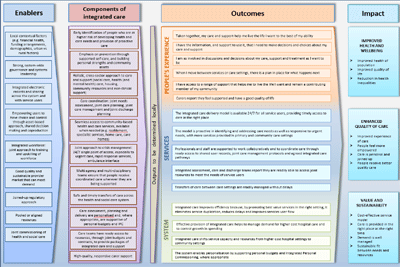

Logic model for integrated care

What good looks like, showing how an integrated health and care system might be structured and function.

Multidisciplinary teams: Integrating care in places and neighbourhoods

Multidisciplinary teams (MDTs) are central to achieving the vision of Integrated Care Systems (ICSs).

"Why are we stuck in hospital?"

Understanding the perspectives of people with learning disabilities and/or autistic people, family and staff.

Prevention in social care

A briefing on prevention in social care and how to encourage people to be more proactive about their health and wellbeing.