Published: March 2015

This guide summarises the process and the key elements to consider in relation to using a strengths-based approach. It should be read in conjunction with the Care and Support (Assessment) Regulations 2014 and Chapter 6 of the statutory guidance.

Prevention services based on a strengths-based approach support an individual’s independence, resilience, ability to make choices and wellbeing.

This guide will be updated and links to further good practice will be added when available.

Key messages

- The Care Act 2014 requires local authorities to ‘consider the person’s own strengths and capabilities, and what support might be available from their wider support network or within the community to help’ in considering ‘what else other than the provision of care and support might assist the person in meeting the outcomes they want to achieve’. In order to do this the assessor ‘should lead to an approach that looks at a person’s life holistically, considering their needs in the context of their skills, ambitions, and priorities’.

- Local authorities should identify the individual’s strengths – personal, community and social networks – and maximise those strengths to enable them to achieve their desired outcomes, thereby meeting their needs and improving or maintaining their wellbeing.

- Any suggestion that support could be available from family and friends should be considered in the light of their appropriateness, willingness and ability to provide any additional support and the impact on them of doing so. This is also subject to the agreement of the adult or carer in question (see 6.64 of the Care Act guidance).

- The implementation of a strengths-based approach within the care and support system requires cultural and organisational commitment beyond frontline practice. Practitioners will need time for research and familiarisation with community resources. Accountability has to be with the practitioner and time has to be allowed for the assessment to be undertaken appropriately and proportionately.

- The objective of the strengths-based approach is to protect the individual’s independence, resilience, ability to make choices and wellbeing. Supporting the person’s strengths can help address needs (whether or not they are eligible) for support in a way that allows the person to lead, and be in control of, an ordinary and independent day-to-day life as much as possible. It may also help delay the development of further needs.

What is a strengths-based approach to care?

Strengths-based practice is a collaborative process between the person supported by services and those supporting them, allowing them to work together to determine an outcome that draws on the person’s strengths and assets.

As such, it concerns itself principally with the quality of the relationship that develops between those providing and those being supported, as well as the elements that the person seeking support brings to the process. [1]

Working in a collaborative way promotes the opportunity for individuals to be co-producers of services and support rather than solely consumers of those services. [2]

A strengths-based approach to care, support and inclusion says let’s look first at what people can do with their skills and their resources and what can the people around them do in their relationships and their communities. People need to be seen as more than just their care needs – they need to be experts and in charge of their own lives.

The phrases ‘strengths-based approach’ and ‘asset-based approach’ are often used interchangeably. The term ‘strength’ refers to different elements that help or enable the individual to deal with challenges in life in general and in meeting their needs and achieving their desired outcomes in particular. These elements include:

- their personal resources, abilities, skills, knowledge, potential, etc.

- their social network and its resources, abilities, skills, etc.

- community resources, also known as ‘social capital’ and/or ‘universal resources’.

What do practitioners need to consider?

Practitioners will need to work in collaboration with service users, supporting them to do things for themselves, with the aim that they become more than passive recipients of care and support. In order to do this, it is fundamental that practitioners establish and acknowledge the capacity, skills, knowledge, network and potential of both the individual and the local community.

Preparing for assessment

Preparing for an assessment is key to ensuring the intervention is conducted professionally, that its effects are maximised and that the assessment is both appropriate and proportionate. When preparing for an assessment you should:

- Gather information and background on the individual’s circumstances:

- What are their reasons for contacting social services?

- Are there any other professionals involved?

- Do the local authority or any partner organisations have any useful background information?

- Is an interpreter or advocate needed?

- Determine, jointly with the individual, how the assessment will be conducted in terms of appropriateness and proportionality.

- Has the individual been informed about what an assessment involves: their options, the timescales, the potential next steps?

- Does the individual prefer to perform a supported self-assessment?

- Agree on who should contribute to the assessment other than the individual and how this will be done.

- If an assessment visit is to take place:

- Has everybody who needs to be there been informed (i.e. care professionals, carers, other family members, friends, etc.)? Have they confirmed their attendance?

- Do you have all the information and paperwork you need?

- Have you done research on related community services, products and activities?

What information is being sought?

The assessment intervention should aim to discover what the person concerned believes would constitute a ‘good life’ for them and their family, and how all parties can work together to achieve this.

In particular the following information should be gathered using open questions rather than a tick-box exercise. The following questions are examples of the type of information that may need to be gathered, although each assessment should be approached on a case-by-case basis, and it may not be necessary or relevant to ask all of the questions suggested here.

- Individual’s strengths, hobbies, abilities, wishes, etc.

- What is the individual good at? What do they enjoy doing? What did they used to enjoy doing but can no longer do?

- What would they like to be better at?

- What do they think they can do better or more of?

- What do they think they can do to improve themselves and their wellbeing?

- What do they think will help, if not to make things better, then at least to prevent things from getting worse?

- Individual’s support network (friends, family, neighbours, professionals, etc.), their strengths, abilities, knowledge, etc.

- Who can they count on? How would they reach them? What would they count on them for?

- Who visits them frequently? How often?

- Who do they miss? Why are they not able to see/keep in touch with these people?

- Who do they communicate with? How? With what frequency?

- Who else do they know that could be part of their lives?

- Are there any other people helping the individual? Any other professionals?

- Is there anything that could facilitate this network to increase, either in quantity or quality? Do they want it to increase?

- What has been working until now, and how have things changed?

- What could help to enable them to return to previous means of support which worked for them?

- Which needs/outcomes can be met/achieved now without waiting for/moving to a care and support plan?

- Needs, challenges, risks, etc. (focusing on strengths does not mean ignoring these, but maximising and using the strengths to overcome them)

- What is preventing the individual from doing what they would like to do or seeing who they would like to see?

- What do they think they can do to change this?

- Who do they think can help to change it?

Practitioners should ensure that they have fully and accurately understood the individual’s views on the above, and ask for clarification when required. ‘Presenting back’ to the individual is a good technique for confirming the accuracy of information. For example: ‘So what I heard you say is …’; ‘Can I check I’ve understood this as you meant it …’.

It is easy to misunderstand what others say, or to only understand it within our own context. When people talk about things they are very familiar with, they often omit information that could be key to understanding fully and accurately what they mean. Practitioners should ensure as far as possible that no information is missing or misunderstood.

Example 1: ease of misunderstanding

Mrs J, a woman who lives on her own, is introverted and has never had any relationship with her neighbours. However, she says that her relationship with them is ‘good’. For her, this means that they never bother her and she has no interaction with them at all. However, the assessor may understand ‘good’ to mean that the neighbours are helpful and that Mrs J could call on them if she was in need of help.

Strengths-mapping

A focused discussion with the person about their strengths can lead to new opportunities to develop and share skills and make new connections. This is sometimes referred to as a ‘strengths-mapping exercise’. This method of assessment builds a picture of the individual’s strengths and of the community around them. There are two types of strength: ‘soft’ and ‘hard’, each of which applies to the individual and the community.

‘Soft’ strengths

Individual

- Personal qualities

- Knowledge and skills

- Relationships

- Passions and interests

Community

- Links with neighbours

- Community groups

- Shared interest groups

- Community leaders

‘Hard’ strengths

Individual

- Health

- Finances

- Housing

- Transport

Community

- Health and social care services

- Leisure

- Schools

- Community buildings

During the assessment it may be helpful to consider the following questions: [3]

- In order to remain as independent as possible, what strengths (knowledge, experience or expertise) does the individual already have and how could these be enhanced?

- In order to enable an individual to remain as independent as possible, what other skills, knowledge, experience or expertise do people directly or indirectly involved in the person’s life already have or need to acquire?

It is also important for the practitioner to have an objective understanding of the individual’s views and to ensure that strengths, needs and outcomes have not been over- or underestimated. In order to do this, it may be necessary to speak to others in the individual’s network (ensuring consent is obtained) and/or seek evidence. For example, it may mean observing or establishing via others an individual’s level of mobility. They may have been living with severely reduced mobility over a long period and become accustomed to the considerable limitations this causes them in their day-to-day life, while an objective understanding gained during assessment would help to reveal the true impact on the individual’s wellbeing.

Example 2: a balancing act

Ms L, 85, is asking for help as she can no longer safely manage her own personal care. During the assessment it emerges that Mrs T, a friend who lives nearby, and who has been providing support until now, including personal care, has suggested that she might not want to continue in future. With Ms L’s permission the assessor talks to Mrs T and discovers that she would in fact be happy to continue if she can be assured that she is doing the right thing and that she would not be expected to do any more if and when the situation changes.

During the discussion it emerges that Mrs T is interested in the option of sharing the provision of support with the local authority. This would allay her concerns about Ms L’s potentially increasing needs, and access to her own support and/or training, along with and further guidance on her caring role, would reassure her that she is ‘doing the right thing’.

It is important in this case for the assessor to explore Ms L’s own view concerning her personal dignity: how does she feel about relying on informal help from someone she knows as opposed to receiving help from a ‘stranger’ from social services? How does she feel about a ‘balance’ of care, as discussed with Mrs T?

The assessor should also ensure that relevant benefits are claimed, such as attendance allowance, which, if appropriate, could be used to pay for informal support. This may in turn help in maintaining Ms L’s dignity by giving her greater control.

What makes a good assessment?

At SCIE we asked a group of people using and receiving services, and a group of carers, to share their experiences of being assessed, and tell us what a social worker could do to make an assessment better. Their answers highlighted the following areas.

- Be flexible and perceptive of an individual’s situation and needs around the assessment process.

- Allow for a break in the assessment if needed so that the user doesn’t become overwhelmed.

- Have an understanding of the person’s condition.

- Repeat facts to confirm they’re accurate and you have noted them down correctly.

- Follow a holistic/whole-person approach.

- Look at the whole community and be aware of the support available from that community.

- Focus on a whole-life approach not just a person’s care needs.

- Focus on outcomes.

- Consider how the individual might contribute to the local community, and hence be better integrated in the wider society around them.

- Be professional, honest, open and approachable.

- Make sure you listen.

- Let people speak, even if their assessment is taking place with an advocate present.

- Be clear that you can’t fix everything in one session and that this is an ongoing process.

- Build trust with people.

- Be conversational without too much direct questioning – people will open up more and provide more detailed answers.

- Be friendly but be aware of the difference between ‘friend’ and ‘friendly’.

- Be clear about who is making any given decision. If you need to take your findings to your manager then be clear about this from the start.

- Let the individual know that they have a right to appeal against the outcome of the assessment.

- Explain the possible outcomes

- Don’t use jargon.

- Perform your assessment as an intervention, so that the individual will benefit from the process itself no matter what the outcome is.

What happens next? Extending a strengths-based approach from assessments to meeting needs

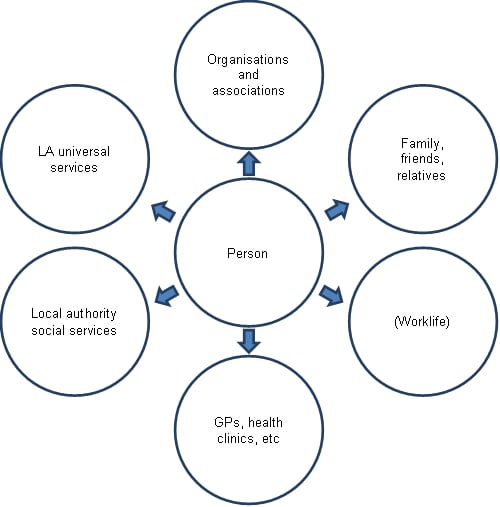

A local authority can extend the use of the strengths-based approach from assessments to meeting needs. Having identified the person’s strengths and resources in the assessment, the assessor will need to consider how these can be deployed at the care and support planning stage in a sustainable way. It may help to think about how the person currently engages with the community and in what way, by mapping their existing contacts, as shown in the diagram below.

Mapping the person’s existing contacts helps to build an understanding of the people and organisations they already interact with and may trust. A person’s confidence is a necessary prerequisite for adopting a strengths-based approach to meeting needs. In order for this approach to be possible and sustainable, the assessor will need to consider whether the person has the necessary strengths, has the capacity to learn and change their way of doing things, and trusts the networks that they will be relying on. It is vital that the person is empowered and is reasonably determined to make things work.

The strengths-based approach can them proceed via:

- Identification of the person’s strengths and capacity as well as their current interactions with the community (as illustrated above) in the assessment.

- Building strengths-based interventions around the person’s outcomes and aspirations identified in the assessment at the care and support planning stage. The strengths-based approach lends itself well to needs related to connecting with people, staying (physically) active, socialising, learning new skills and/or offering skills or knowledge to others in the community. When the strengths-based approach is executed well, informal networks can be utilised to meet the more practical needs of the individual. This is why it’s important that the person’s networks are identified in the assessment.

- Finding solutions in the community or social environment at the care and support planning stage. In order for this to be possible, the community needs to be seen as resource-rich. It may help to think of resources in terms of actual support services, informal support with care tasks, time, finances, information, advice or knowledge.

These three steps show how the assessor, the commissioner and the care manager need to work together. The assessor needs to identify strengths, harness these to achieve positive change and build support relationships that can make the intervention planned by the commissioner sustainable.

Finding solutions in the community may appear to be a daunting task. For a local authority to reap the benefits of a strengths-based approach, it may help to think of it not as a task, done just for the given individual, but as a strategy that is pursued for the benefit of everyone who approaches the local authority and for the benefit of the wider community. There are a number of ways for assessors, commissioners and care managers to establish community strengths and resources, and two examples follow: local area coordination and community strengths-mapping.

Local area coordination

Local area coordination is an approach to assisting local people (including those with care and support needs) to build their personal or family vision and take action for a good life by supporting them to stay strong, safe and connected. With a focus on strengths, aspirations and contributions, the person or family are empowered to build and sustain their networks locally, thus nurturing resilience and independence.

Local area coordinators work in defined communities to support the building of strong local relationships and contribute to sustainable, inclusive and supportive communities. They support individuals to draw on their personal and family resources to solve issues and connect with others who might be able to assist. They also help the person to identify the things they have to offer so that support becomes mutual. This fits into the overall approach of the Care Act to reduce, prevent, and delay the need for intervention.

An example of how a local authority in England has implemented this approach can be seen in Local area co-ordination: supporting transformation in Derby.

Community strengths-mapping

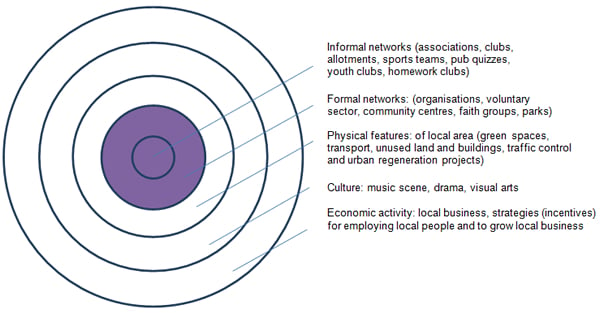

Community strengths-mapping is an exercise which can help local authorities conceptualise and describe community strengths. The diagram below sets out how a local authority might think about the community resources that exist around the person. The person’s own contacts in the community may include formal and informal networks (i.e. personal relationships in the form of clubs and/or memberships of organisations). The steps a local authority might take in mapping, negotiating and facilitating access to community strengths might follow this progression:

- Meet the people in the person’s support network (especially where the person has flagged that they have informal networks) to explore what resources (time, capacity, skills and knowledge) might be available to help the person.

- Contact people who are active in the community (especially formal networks that are relevant in the person’s daily life) and establish what scope there is in the organisation to adapt to the person’s, or indeed the local, need. It may for instance be possible to organise collective transport for people who attend church services together. Where a local authority doesn’t have local area coordinators, health visitors might be a means of identifying people who are engaged in their local area.

- Recruit. Develop local clubs and organisations by supporting people who are active in the community to engage more people.

- Use those networks to identify needs and resources. Identifying needs that are not being met is a positive outcome for local authorities that want to develop local organisations. Where there is a collective need, there is a possibility for an organised response.

- Map the resources. Ensure that there is a contacts directory which is maintained and enables more people to get in touch easily.

- Maintain contact with local activity leads. By building multi-agency partnerships, engagement can be sustained and the reach of the organisation expanded.

The diagram below illustrates how commissioners can consider community strengths and resources in terms of what exists around the person being assessed. The purple circles show where people come together outside the local authority’s sphere of direct influence. People’s activity has an impact on other spheres of public life (the white circles), which the council can influence through broader strategic public spending. Assessors can go so far in identifying existing resources, but if a broader strategy to develop local activities is employed, then more spheres can be ‘opened up’, allowing the strengths-based approach to meeting needs to become better resourced and more sustainable.

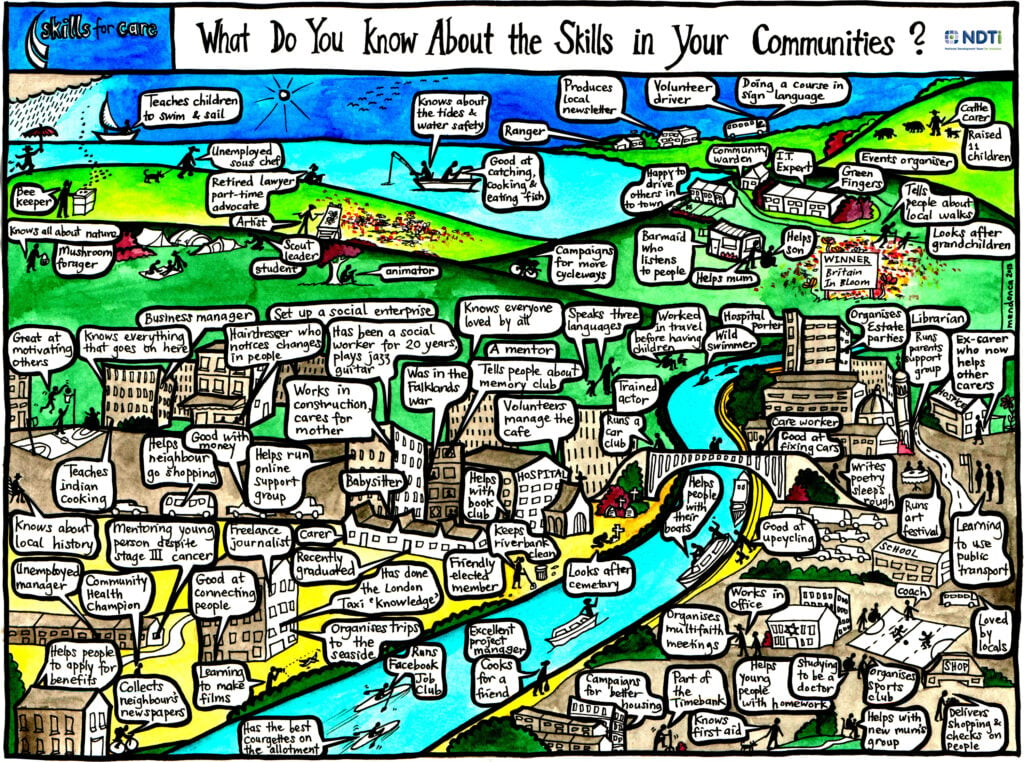

As the picture below illustrates, our communities are full of people with diverse skills, qualities and life experiences, but this may not always be recognised. Another element of adopting a strengths-based approach is to recognise skills within the community.

Very often it is formal qualifications or professional expertise that are valued, when in fact it is attributes and qualities such as local knowledge, communication skills and a desire to contribute and participate that assist our communities and permit the individuals within them to thrive.

The strengths-based approach starts with the premise that all of us have something to offer, including people who need support to participate fully in the community, and even people nearing the end of their lives.

Having created an overview of the person’s and the community’s resources, the assessor and the commissioner can overlay the person’s needs and skills with those in the community and, in this way, integrate the individual in the wider community. Skills for Care has developed a method for achieving this called ‘Skills around the person’. [3] More information can be found on the Skills for Care website.

Implications for practice

The strengths-based approach will in many places result in a cultural shift, with the local authority focusing on the person’s strengths and abilities. It means thinking positively about people who need care and support as well as engaging with the community to reduce isolation and draw those with care and support needs further into community networks. The strengths-based approach is about reducing dependency and challenging ‘prescription culture’. Crucially, it is about protecting and promoting the person’s independence, resilience, choice and wellbeing.

The Care Act requires local authorities to have a strengths-based approach throughout the user’s journey and enshrined within all interventions/interactions with individuals. Here are some of the implications for practice.

- Practitioners need to have greater knowledge and awareness of community resources and social capital, particularly within the area in which they work. Managers should allow time for practitioners to research and gain this knowledge.

- Practitioners must prepare assessments thoroughly. Time for preparation of assessment should be taken into account for performance purposes and definition of workloads. Other changes in assessment methods (e.g. supported self-assessment, third-party assessment and improved prevention) should provide opportunities to regain time.

- Assessment should be a collaborative process of gathering information through a conversation drawn from open questions with the individual.

- Assessments should be outcome-based and not output-based – i.e. they are about what needs to change rather than what someone needs to do.

- Senior management, middle management and practitioners will have to make adjustments and allowances to accommodate strengths-based practice. The key implications of this will be:

- assessments (including preparation and closure) could take longer

- accountability and decision-making are delegated to frontline staff, following a competency-based approach to ensure staff are confident and competent to work in this way

- monitoring and review, and therefore performance measures, should focus on the impact of interventions in improving/changing outcomes for individuals

- the need to establish where the process can be streamlined to free up time (e.g. identifying process bottlenecks such as mandatory sign-off or unproductive handovers; offering supported self-assessment and planning for those who do not need local authority intervention; making better use of partners as trusted assessors).

Checklist of core duties for local authorities

The checklist below provides a brief summary of the core duties in relation to conducting a strengths-based assessment. It should be read in conjunction with the Care and Support (Assessment) Regulations 2014 and Chapter 6 of the statutory guidance.

Local authorities must:

- Provide or arrange for services, facilities or resources which will prevent, delay or reduce individuals’ needs for care and support or the need for the support of carers.

- Carry out an appropriate and proportionate assessment.

- Carry out a capacity assessment if they believe an individual may lack capacity.

- Support the individual to be involved in the assessment. This involves providing as much information as possible from the time of first contact, in an accessible format, so that the individual undertaking the supported self-assessment has a full and clear picture.

- Involve an advocate (a family member, friend or independent advocate) to help the individual through the process if they have substantial difficulty understanding, retaining and using the relevant information.

- Ensure the assessment is undertaken by a practitioner who is appropriately trained and has experience of the condition, or consults someone who has. If the user is deafblind the practitioner must have specialist training to carry out the assessment.

- Carry out a safeguarding inquiry where a person may be at risk of abuse or neglect.

- Consider what else (other than the provision of care and support) might assist the person in meeting the outcomes they want to achieve.

- Ensure the care and support plan, or support plan, is, as far as possible, agreed by the adult or carer in question.

Video: What is a strengths-based approach?

What is a strengths-based approach?

Useful resources

- Think Local Act Personal: The Royal Society of Arts has published ‘The new social care: strengths-based approaches’, edited by TLAP co-chair and Shared Lives Plus CEO, Alex Fox.

- Tools such as the ROPES (resources, opportunities, possibilities, exceptions, and solutions) model4 have been developed to guide practitioners in a broader process of continually drawing on strengths. Using frameworks focused on strengths and weaknesses encourages a holistic and balanced assessment of the strengths and problems of an individual within a specific situation.

- Graybeal C (2001) ‘Strengths-based social work assessment: transforming the dominant paradigm’, Families in society: the journal of contemporary human services.

- Berg, C.J. (2009) ‘A comprehensive framework for conducting client assessments: highlighting strengths, environmental factors and hope’, Journal of Practical Consulting, vol 3, no 2, pp 9–13

- ‘Care bill paves way for strengths-based approach to care’

- Community Catalysts, In Control, Inclusion North, Inclusive Neighbourhoods, Partners in Policymaking, Shared Lives Plus (2014) Strengths-based approach in the Care Bill.

- Institute for Research and Innovation in Social Services (2012) Insight: Strength-based approaches for working with individuals.

- Skills for Care (2014) Skills around the person: implementing asset-based approaches in adult social care and end of life care.

- Improvement & Development Agency and the Local Government Association (2010) A glass half-full: how an asset approach can improve community health and wellbeing.

References

1 – Duncan, B L and Miller S D (2000) ‘The heroic client: doing client-directed outcome-informed therapy’, San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

2 – Morgan A and Ziglio E (2007) ‘Revitalising the evidence base for public health: An assets model’, International journal of health promotion and education, Supplement 2,17–22.

3 – Skills for Care (2014) Skills around the person, Leeds: Skills for Care.

4 – Graybeal C (2001) ‘Strengths-based social work assessment: transforming the dominant paradigm’, Families in society: the journal of contemporary human services, 82, 233–242