Published: September 2024

Authors: Bryony Beresford and Chunhua Chen, Social Policy Research Unit, University of York

Reablement services support older people to keep their independence and stay living in their own homes. For older people to gain maximum benefit, they need to actively engage with being reabled. Reablement services tell us that this can be difficult to achieve.

This resource sets out evidence-informed guidance on addressing the barriers to securing, maintaining and maximising older people’s engagement with reablement, and the support and collaboration of family members. It draws on findings from a national study into client and family engagement with reablement (the EAGER project) led by the University of York and funded by NIHR’s School for Social Care Research.

The team at York have worked with the Social Care Institute for Excellence to disseminate the study findings and this resource to the social care sector.

Section 1: What do we mean by engagement with reablement?

What is reablement?

Reablement is an intensive, time-limited intervention delivered in people’s homes. Its aim is to support people to regain the skills and confidence needed to manage daily life and do the things that are important to them. This can include finding new ways of doing everyday tasks, sometimes through introducing simple aids and equipment.

What is engagement?

Engagement is the term used to describe how much someone ‘buys into’ an intervention they are receiving and actively participates in their ‘treatment’.

It’s used across of lots of different services and settings, including rehabilitation, mental health therapies and education/learning.

Why is engagement with reablement important?

Poor engagement or resistance to reablement is something reablement services frequently face. How much someone engages with being reabled affects how successful reablement is. Managing poor engagement or resistance to being reabled can be challenging and time-consuming for staff.

Why don’t people engage with being reabled?

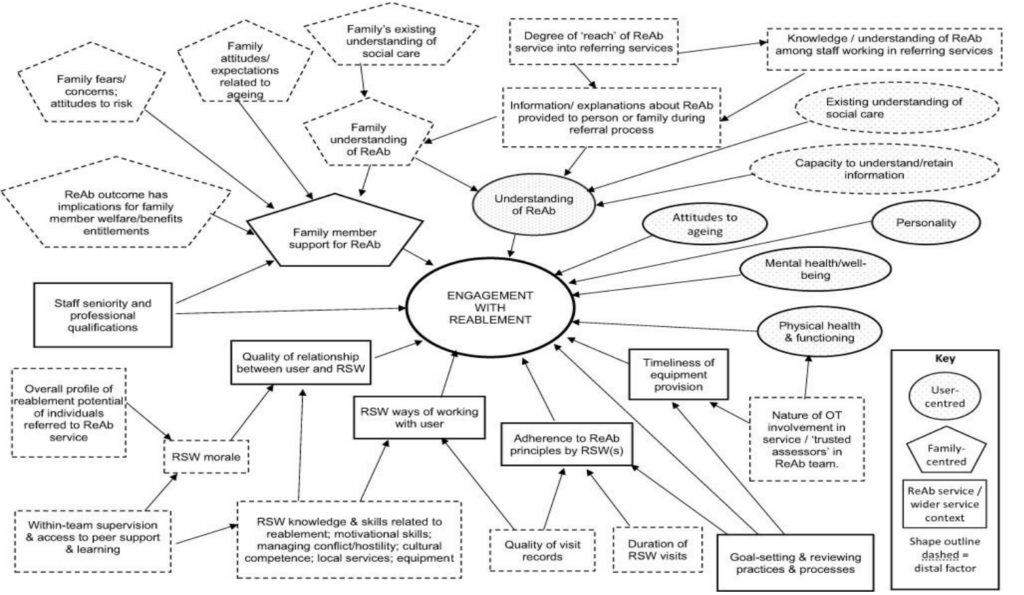

There are lots of reasons why older people don’t engage with being reabled, and families can be unsupportive, see Figure 1 below.

These range from poor public understanding of social care through to the way reablement services are organised, how family members respond to reablement, the relationship between reablement staff and people who draw on care and support, and their attitudes and personalities.

Figure 1:

Factors affecting engagement with reablement (reproduced from Chen, C. & Beresford, B., Factors impacting user engagement in reablement: A qualitative study of user, family member and practitioners’ views, J Multidiscip Healthc. 2023; 16: 1349–1365).

Section 2: How this resource can help with reablement

What is this resource?

It’s clear that some of the factors affecting whether someone engages with reablement aren’t things local services, on their own, can do much about (e.g. public attitudes to ageing). However, there are things they may be able to change or improve which can positively impact engagement with reablement.

This resource offers evidence-informed recommendations on how to address or manage these sorts of issues.

Different sources of evidence have been used to create it, including:

- research on reablement.

- wider research on supporting understanding of care and treatments and intervention engagement.

- cumulative experiences of reablement practitioners and good practice guidance.

- consultation work with older people on information provision.

This resource covers two core issues:

• supporting understanding of reablement (see section 3)

• supporting engagement and managing resistance (see section 4).

Some recommendations are low-resource, ‘quick wins’, others are low-resource but require planning and integration into usual systems and processes. Some can be implemented by reablement teams, others require some form of joint-working with other services.

Unless the existing evidence is sufficiently robust, recommendations requiring substantive levels of investment or joint-working, or may disrupt existing delivery models, are avoided. Care has been taken to ensure the content is relevant across different service-delivery models.

Who should be using this resource?

This resource is for:

• reablement service managers.

• strategic leads for reablement, including those involved in commissioning reablement services.

• strategic leads within integrated care systems with responsibility for older people’s social care and hospital discharge processes.

How to use this resource

The resource has been designed so that it can be ‘dipped into’ or used as a tool to support a more comprehensive review of current systems and practices relevant to supporting understanding of and engagement with reablement.

How is the resource organised?

Sections 3 and 4 set out evidence-informed recommendations on the key issues relevant to understanding of, and engagement with, reablement. Sections 5 to 7 provide additional materials.

Box 1: Overview of the EAGER resource

Section 3: supporting understanding of reablement

- Ensuring accurate and consistent messaging from ‘first mention’ onwards.

- Using high quality information resources.

- Using job titles to promote understanding of reablement.

- Reaching into referring services.

- Improving public understanding of reablement.

Section 4: supporting engagement and managing resistance

- Training and supervision of frontline reablement staff.

- Promoting family member ‘buy-in’ and support for reablement.

- Embedding effective goal-focussed working across the reablement pathway.

- Timely equipment provision.

- Nurturing morale and motivation in frontline staff.

- Managing anticipated loss of companionship.

Sections 5 to 7: Additional tools and guidance

- Service mapping and review tools.

- Guidance on creating information leaflets.

- Guidance on creating information videos.

Section 3: Supporting understanding of reablement

Reablement services often find that older people and their families don’t understand what reablement is and how it works, or don’t remember having it explained to them.

There are things which reablement services can do to help ensure that people being referred to reablement understand its purpose and how it works. These are:

• Ensuring accurate and consistent messaging from ‘first mention’ onwards.

• Using high quality information resources.

• Using job titles to promote understanding of reablement.

• Reaching into referral services.

• Improving public understanding of reablement.

Ensuring accurate and consistent messaging from ‘first mention’ onwards

Typically, older people and their families first hear about reablement from another professional or service (e.g. NHS discharge teams, GP, ‘first point of contact’ services). However, they may not understand what reablement is and, particularly, how it differs from long-term care. As a result, older people and their families are misinformed.

In some localities, NHS staff are referring to reablement services in a number of different local authorities. However, these local authorities may call their reablement service different things. This is confusing for staff.

Box 2 sets out some recommendations for supporting consistent messaging across the referral and care pathway. Specific recommendations regarding the content and design of information leaflets/videos is covered in the next section.

Box 2: Ensuring consistent messaging from ‘first mention’ onwards – recommendations

- Check what reablement services are called by other local authorities also receiving referrals from the hospital(s) referring into your service. (See section 5: review tool 2). Consider working with these local authorities to develop a common set of terms/vocabulary in terms of service name, staff job titles and description of the reablement delivery process.

- Request referring services to implement a generic social care module and reablement-specific module in induction programmes for (relevant) staff.

- Consider a poster information campaign in staff areas. Content should include: the objectives of reablement, how reablement is delivered, the difference to ‘traditional’ home care, evidence on effectiveness and cost-effectiveness.

- Consider running a reablement service ‘open day’ for professionals based in referring services. Run these on an occasional but regular basis.

Create a standard script about reablement for insertion into discharge planning tools. Where a service refers to reablement services in multiple local authorities, ensure ‘reablement scripts’ are correct/relevant for all relevant reablement services.

- Use the same information leaflets across referral and intervention pathways.

- Consider using a ‘Welcome Home from your Reablement Service’ card which is left after the first visit by the reablement service. Attractively and clearly designed, and stood on a table or other surface, this acts as a clear and distinctive reminder.

Using high quality information resources

Many older people and family members do not recall receiving an information leaflet about reablement even though it is likely they would have been given or offered one on at least one occasion. Delirium, heightened stress and anxiety and overwhelming desire to ‘get home’ can affect older people’s capacity to understand or retain information during the referral process.

High quality and meaningful information resources – provided on multiple occasions – can help to overcome this, see Box 3.

Box 3: Information resources for older people and their families – recommendations

- The primary information resource should be a well-designed, easy to read information leaflet.

- See section 6 for guidance on leaflet design and readability, including tools to assess existing information leaflets, and suggested ‘core text’ developed in consultation with older people and family members.

- See section 6 for guidance on leaflet design and readability, including tools to assess existing information leaflets, and suggested ‘core text’ developed in consultation with older people and family members.

- There should be separate information leaflets for older people and family members.

- If contact details of family members are recorded, request permission to share information resources (e.g. pdf, hyperlink) via text message/email.

- Leaflets should include the following content:

- clear statement of the objectives of reablement.

- clear description of how reablement is delivered.

- clear explanation of how it differs to ‘traditional’ home care.

- evidence on effectiveness of/preventive nature of reablement.

- evidence on benefits of being as independent as possible.

- explicit reference to possible concerns/sources of resistance, and reassurance regarding these.

- an acknowledgement that the referral is an indicator of a possible ‘transition’/turning point in life and/or roles/relationships within the family.

- clear statement of the objectives of reablement.

- Actively offer information leaflets to the older person/family member on multiple occasions including:

- when a referral to reablement is first mentioned.

- during the assessment/goal-setting visit.

- at the first visit by a reablement support worker.

- when a referral to reablement is first mentioned.

- Where possible, staff should ‘talk through’ the leaflet rather than simply hand it over.

- Videos should not be used as the primary means of conveying information. However, they may be a useful additional resource. Section 7 of this resource sets out advice on the format and content of information videos for reablement clients and their families.

Using job titles to promote understanding of reablement

Older people (and their families) with no previous experience of reablement are unlikely to understand that reablement is, in essence, a complex intervention delivered by skilled staff, and that it is entirely different to long-term care. The job titles carry implicit messages about a role, and those used by reablement services can either support or contradict the ethos and objectives of reablement, see Box 4.

- Avoid the use of ‘care’ in job titles (e.g. ‘reablement care worker’, ‘care and support worker’) as these may foster expectations of a ‘traditional’ homecare.

- Consider alternatives to ‘worker’ which more explicitly convey the skilled nature of the role of frontline staff (e.g. reablement practitioner).

Increasing the reach into referring services

Commissioning arrangements and reablement service capacity are both factors that affect the presence or visibility of reablement services in referring services.

Currently, there is no UK research evaluating whether integrating reablement services early in hospital discharge pathways addresses issues of understanding of, and engagement with, reablement, nor its effectiveness or cost-effectiveness. Given implementing such a change would be a very significant undertaking, we do not make any recommendation regarding this.

Improving public understanding of reablement

Older people and their families often have a limited, and sometimes incorrect, understanding of social care and are unaware of reablement. Overcoming existing assumptions and expectations can be challenging. Addressing this issue requires sustained national level action and investment. However, actions are possible at a local level, see Box 5.

Box 5: Improving public understanding or reablement – recommendations

- Consider targeted public information campaigns (posters, information videos) about social care, including the differences between reablement and ‘traditional’ homecare.

- Potential settings for such campaigns include GP surgeries, hospitals (public corridors, emergency and outpatient departments, wards), libraries and community centres, supermarkets.

- In addition, or alternatively, identify existing community groups willing to host/coordinate information sessions and distributing information resources.

- Potential settings for such campaigns include GP surgeries, hospitals (public corridors, emergency and outpatient departments, wards), libraries and community centres, supermarkets.

- Consider approaching local/regional news programmes and print media to broadcast/feature a piece, or short series, on reablement. Achieving this may not be as difficult it is might first appear. Social care is highly topical, and media organisations are often looking for ‘good news’, ‘people-focused’ stories. They will also lead on, and bear the costs of, creating the content.

Section 4: Supporting engagement and managing resistance

Whilst understanding of reablement is a key factor affecting engagement with reablement, a number of aspects of reablement service practice can also impact engagement.

This section focuses on what reablement services can do to secure, maintain and overcome resistance.

It covers the following issues, including evidence-informed recommendations:

- Training and supervision of frontline reablement staff.

- Promoting family member ‘buy-in’ and support for reablement.

- Timely equipment provision.

- Nurturing morale and motivation in frontline staff.

- Managing anticipated loss of companionship.

Training and supervision of frontline reablement staff

Reabling someone is a highly skilled job, requiring staff to establish trusting and collaborative relationships with clients in a short period of time, to be skilled in identifying how best to motivate and encourage individual clients, to make ‘in the moment’ judgements and decisions, and to be responsive and creative in the way they work with and support clients. All these skills support client engagement with reablement.

Staff also need to be skilled in managing resistance and conflict – either on the part of the client or family members. To some extent, such skills are acquired over time (experiential learning). However, didactic training also has its place.

Box 6: Training and supervision of frontline reablement staff – recommendations

- Ensure induction includes training on the principles and practices of reablement via high quality training modules and experiential learning.

- Develop and facilitate opportunities for sharing knowledge and problem-solving within the team:

- Offer regular individual and/or group supervisions.

- Set up systems/processes which support ad hoc communication between front-line staff involved with clients (e.g. WhatsApp group).

- Incorporate regular peer learning opportunities for reablement staff which facilitate exchange of knowledge, skills and experience from more experienced staff to those newer to the service.

- Provide specialist training in motivational interviewing and conflict management to staff (senior and ‘frontline’). Generic training on these issues is already available and being used by local authorities. However, additional input to support application of core skills and principles to the reablement context, by senior reablement staff or trainers is required.

- Ensure there is a clear and efficient process by which user resistance or conflict is managed and escalated within the service. Be clear that recourse to support from senior colleagues is acceptable and encouraged.

Promoting family member ‘buy-in’ and support for reablement

Reablement services are more likely to describe relationships with family members as unsupportive or challenging than collaborative and supportive. However, wider evidence suggests family members can be an important source of motivation and encouragement.

- Where appropriate, assessors/senior staff should seek direct communication with the ‘key contact(s)’ in the family. Conversations should address concerns and knowledge gaps.

- Family-specific information resources should be used to reinforce information shared during these conversations. Information resources should include explicit reference to the potential role of family members in supporting the reablement process.

- Where appropriate, staff (reablement support workers and senior staff) should seek opportunities to involve family members in supporting client’s reablement. This may include:

- encouraging family members to notice and ‘celebrate’ progress

- encouraging family members to remind the client about their goals

- advising family on activities/actions which should be practised or the client can be encouraged, in a safe way, to be more independent

- Where appropriate, offer or sign-post to ‘reassurance technologies’ (e.g. sensors) to allay or pre-empt concerns re client safety.

- Ensure there is a clear action plan for reablement support workers to implement when facing resistant family members. This should include rapid access to and, if required, involvement of senior staff.

Embedding effective goal-focused working across the reablement pathway

Reablement is a goal-focused intervention. However, there are lots of things that can get in the way of effective goal setting, including:

• professionals dominate the conversation or make assumptions

• people who draw on care and support do not understand what is happening or feel unprepared

• goals are set which are not meaningful

• unrealistic goals are set.

A goals-focused approach is also threatened if reablement support workers do not make explicit reference to them, using them to motivate clients or explain why particular actions/activities are being worked on. Ensuring each visit builds on work and progress achieved in previous reablement visits is also important to securing or sustaining engagement with reablement.

In addition, when reablement follows hospital discharge, a period of recovery and adjustment may be needed before a client’s potential can be properly assessed and they are ready to actively engage in reablement.

Box 8: Embedding goals-focused working across the reablement pathway – recommendations

- A two-stage approach to assessment and goal-setting is strongly favoured by those services using this approach. Ideally, the period between assessment visits should be guided by the assessor’s judgement on the time required for client recovery and adjustment. At the first assessment visit, generic goals which reinforce the ethos of reablement are introduced. At the second assessment visit, set individualised and meaningful goals.

- Review the quality of training on goals-focused assessment provided to reablement assessors within the service.

- Implement or review training of reablement support workers on goals-focused working, including explaining the connection between particular actions/activities and the client’s goals, explicitly noting and celebrating achievements/progress towards goals.

- Consider how reablement goals (and progress towards) can be clearly displayed in clients’ homes, and in a way which is accessible to the client and family.

- To support consistency of approach, and building on progress made, ensure the format of ‘client care/reablement records’ allows for easy recording of activities/actions and progress against goals.

- Ensure reviews are explicitly structured around the client’s goals.

Timely equipment provision

Not having the equipment required to begin working on reablement activities/actions, or build on progress made, can be discouraging. On the other hand, even simple pieces of equipment can sometimes offer the immediate reward of easing the effort of achieving a daily task or even managing it independently (e.g. simple dressing and bathing aids, modified cutlery). Such experiences can serve to encourage and motivate wider engagement with the reablement process. Outside of assessment and reviews, frontline reablement workers are in a position to identify an equipment need. However, they may be unaware of the range and types of equipment available.

Not all reablement services have an OT, and arrangement with community OT services varies. Given changing the nature of OT involvement in a reablement service may not be an option in some localities, or making such a change would be a very significant undertaking, we do not make any recommendation regarding this. The recommendations we make, therefore, focus on supporting timely provision of equipment regardless of the nature of OT involvement.

Box 9: Timely equipment provision – recommendations

- Consider working with community OT services to introduce ‘trusted assessor’ roles within the reablement service.

- Consider ways by which non-OT qualified staff can be regularly informed about equipment options and possibilities (e.g. ‘standing item’ in team meetings/supervisions; email updates; hard copies of brochures placed in staff meeting places).

- Consider introducing the facility for reablement support workers to have access to a small budget by which to directly purchase/request the purchase of ‘non-prescribed’ equipment (i.e. not requiring OT assessment) from ‘mainstream’ local or online suppliers.

Nurturing morale and motivation in frontline staff

We know that staff morale and motivation impacts patient/client engagement. Within reablement, there are multiple threats to the morale and motivation of frontline staff, some of which are outside of the control of senior staff and managers. However, there are a number of strategies which reablement support workers say they value, these are set out in Box 10. See also Section 4 on training and supervision.

Box 10: Nurturing morale and motivation in frontline staff – recommendations

- Identify ways in which reablement support workers core role and contribution is explicitly recognised. For example, involving them in review processes, routinely use supervision and team meetings to acknowledge the skills and achievements of frontline staff.

- Consider introducing systems which ensure frontline staff receive updates on clients or service performance.

Managing anticipated loss of companionship

Older people value and enjoy the companionship offered by visits from frontline reablement staff. For some clients, anticipating the loss of visits from reablement staff can result in them disengaging from the process of being reabled. See Box 11 for recommendations on how to reduce the risk of this happening.

Box 11: Managing anticipated loss of companionship – recommendations

- Include mapping of community and social networks within the assessment process.

- Seek to include social outcomes within goals setting.

- Seek to incorporate (re-)connecting clients with social networks and activities within the reablement process, where possible drawing on the support and involvement of family and members of the local community.

Section 5: Service mapping and review tools

Review tool 1: Reflecting on your referral pathways

Use this tool to map out the health and social care services that refer to your service, the issues or challenges in clients/families’ understanding of reablement you’ve experienced, and possible solutions.

Review tool 2: Mapping what nearby reablement services are called

We know reablement services are called different things. This can be confusing for hospitals, particularly when discharging to reablement services in a number of different local authorities. Use this tool to record what other reablement services in your area/region are called.

Section 6: Creating information leaflets

What’s best: Paper leaflets or digital/online versions?

Health research consistently finds that older patients, in particular, are more likely to access and prefer to use paper information leaflets rather than online versions. Reading printed text is less demanding than digital text. People also retain factual information better if they have read printed text.

Leaflet design: What are the key things to get right?

The internationally recognised Barker Able Leaflet Design (BALD) criteria set out the things that help to make a patient information leaflets good quality and effective.

While not all these criteria may apply to social care, they can be useful when reviewing existing information leaflets as well as guiding and informing the development of new leaflets. You can download their simple information leaflet assessment tool below.

Leaflet design: Views of older people

We asked members of the Elders Council of Newcastle to critically review four reablement service information leaflets produced by local authorities. These were deliberately selected to represent different layout features. They made the following recommendations on the design and layout of reablement service leaflets, see Box 12.

Box 12: Older people’s recommendations on leaflet design

- Use white, non-glossy paper.

- Use colour, but limit the number of colours to two or three. Green is a good colour to include.

- If text is placed on a coloured background, make sure there is sufficient contrast.

- Use level 1 headings only.

- Use images (photographs or pictures), but make sure they:

- reflect the diversity of the user population;

- portray reablement (e.g. image reablement staff working with a client) rather than generic images of older people;

- together portray a number of different reablement activities;illustrate the text they are placed alongside;

- convey ageing in a positive way

- if pictures are used, make sure are not too ‘cartoon-y’/lacking in seriousness.

- Use a folded format (rather than single sheet), with a ‘front cover’. Bi-fold (rather than tri-fold) is likely to be easier to use/follow.

- The front cover should include an image and name of the service. Consider using a strap-line under the service name which conveys the objectives of reablement.

- Include quotes of those that draw on care and support. These add a ‘personal touch’ and can be used to authentically convey the potential impacts of reablement.

Leaflet content: The key principles

The key principles are:

- Information leaflets should be readable.

- Information leaflets should be meaningful.

Readability: This can easily be assessed using the Flesch Reading Ease Score. This score is based on two factors:

- sentence length (as judged by the average number of words in sentence)

- word length (as judged by the average number of syllables in a word).

Microsoft and Google offer functions to assess document readability using the Flesch formulae.

An additional, or alternative, tool is the Simple Measure of Goobledygook (SMOG) which assesses the proportion of words with three or more syllables. (This downloadable resource (p.10–11) provides simple instructions on how to calculate SMOG scores.)

Meaningful information: High quality information leaflets address the concerns, questions and priorities of the intended audience. They also contain information that someone needs to know if they are to benefit most from the care or support they will be receiving.

This means those developing information leaflets should:

- consult with and involve people who draw on care and support (and their families)

- draw what’s been learnt already (via research and consultation work) about what information leaflets need to contain.

When and how should information leaflets be given to people?

We know from research an information leaflet works best when:

- it is given to someone at the same time as the information is being given to them verbally and not at the end of the conversation,

- or if previously received, a member of staff reads through it with them.

- And….

- as the information leaflet is read together, staff take care to tailor the information. For example:

- drawing attention to particular sections

- re-phrasing verbally or providing additional explanation

- underlining or highlighting sections of text which are particularly relevant.

The views of older people we consulted with strongly aligned with these recommendations.

Section 7: Creating information videos

What role can videos play in helping people understand about reablement?

Videos can be used to provide the same content as information leaflets. However, they should also be used alongside leaflets.

Videos can also be used as additional information resource, particularly for conveying experiential information (e.g. personal experiences of living with a diagnosis). We know that some, but not all, people find this sort of information useful. However, for services with varied caseloads, such as reablement, it is very difficult to present case-based stories which are meaningful to everyone.

Key principles to follow when creating videos are they must be:

- Short: under 90 seconds (ideally), and no more than two minutes.

- Simple: focused on conveying one message or ‘learning point’.

- Authentic.

- Accessible to the target audience in terms of:

- pacing (i.e. cognitive demand) – providing sufficient time to follow and process information;

- hearing – certain voice pitches or background music behind a voiceover make it harder to hear, particularly among older people;

- vision – the ability to see outlines and differences in shading declines with age; captions/subtitles must take account of possible sight impairments.

Older people’s views on reablement information videos

We asked members of the Elders Council of Newcastle to critically review four information videos produced by local authorities. These were deliberately selected to represent different styles (film vs animation), duration (one to four (plus) minutes) and ‘narrator’ (older person vs staff).

The video which they thought worked best was:

- One minute long.

- An animation using the voiceover of a person that draws on care and support in a local accent.

- Used a text ribbon/captions.

- Effectively covered:

- goal-setting

- the role of support workers

- focus on supporting daily living with aim of regaining independence

- reducing duration/intensity of visits from support workers and discharge

- use of equipment

- wider outcomes, including mental health and building of confidence.

Key drawbacks or limitations of the videos they reviewed are summarised in Box 13.

Box 13: Drawbacks or limitations of existing reablement service information videos

- too long (longer than two minutes)

- inaccurate or uninformative title

- too much jargon, not in plain English

- lack of diversity

- use of ‘real life’ cases made the information too case-specific

- people who draw on care and support that are used in films are typically middle class and very articulate

- too detailed, or key information missing

- inclusion of irrelevant information (e.g. commentary wide range of other services)

- overly focussed on mobility issues as reason for referral and focus of reablement

- use dated or stereotypical animation

- lack of user perspective

- boring, uninspiring

- patronising tone.

Acknowledgements

This Resource is an output of the EAGER project which was carried out by researchers at the University of York. Staff in reablement teams in England and Wales contributed to the evidence base on which this resource was based. Many also provided reflections, feedback and suggestions as the content of the resource was being developed. The research team also worked with members of the Elders Council of Newcastle to develop Sections 6 and 7 of the resource.

The EAGER project was funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR’s) School for Social Care Research (SSCR). The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the SSCR, NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.